By

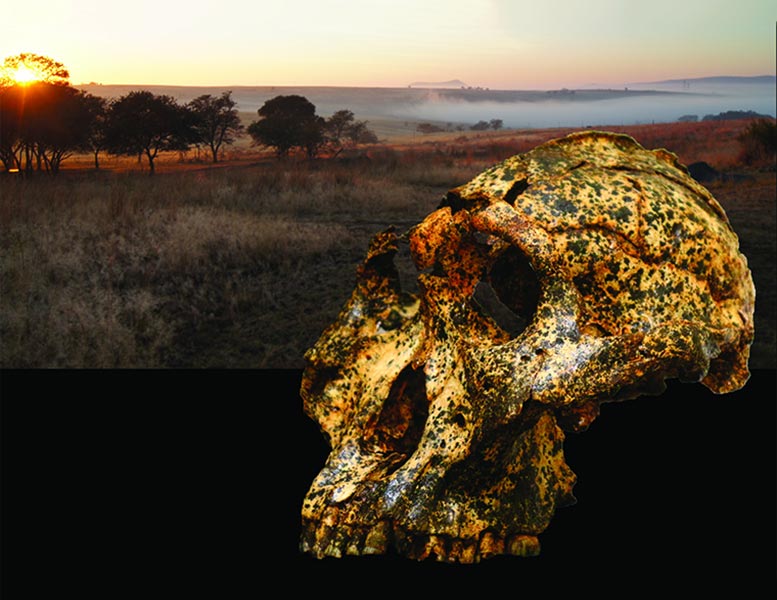

The discovery of a remarkably well-preserved fossil from the extinct human species Paranthropus robustus suggests rapid evolution during a turbulent phase of local climate change, resulting in anatomical changes previously attributed to gender. Photo credit: Courtesy of Jesse Martin and David Strait

Fossil skull suggests that environmental conditions led to rapid changes.

Male of the extinct human species Paranthropus robustus were viewed as significantly larger than women – similar to the size differences observed in modern primates like gorillas, orangutans, and baboons. But a new discovery of fossils in South Africa suggests so P. robustus developed rapidly during a turbulent period of local climate change about 2 million years ago, resulting in anatomical changes previously attributed to gender.

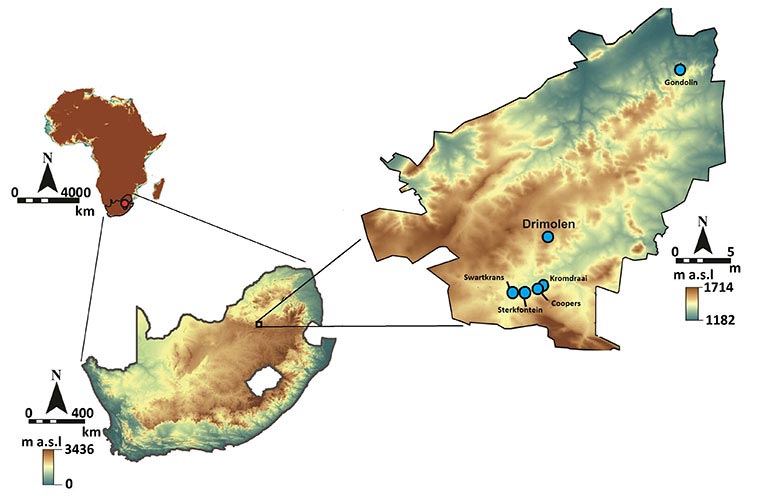

An international research team, including anthropologists from Washington University in St. Louis, reported in the journal about their discovery from the fossil-rich Drimolen cave system northwest of Johannesburg Natural ecology & evolution today (November 9, 2020).

David Strait. Photo credit: WUSTL

“This is the kind of phenomenon that is difficult to document in the fossil record, especially in relation to early human evolution,” said David Strait, professor of biological anthropology in Arts & Sciences at Washington University.

The remarkably well-preserved fossil described in the newspaper was discovered by a student, Samantha Good, who attended the Strait-run Drimolen Cave Field School.

Researchers already knew the appearance of P. robustus in South Africa coincided with the disappearance of Australopithecus, a somewhat more primitive early man, and the emergence in the region of the early representatives of homo, the genus modern humans belong to. This transition happened very quickly, perhaps within a few tens of thousands of years.

“The working hypothesis was that climate change is causing stress in the population of Australopithecus This eventually led to her death, but the environmental conditions were more favorable to her homo and Paranthropusthat may have dispersed into the region from elsewhere, ”Strait said. “We can now see that the environmental conditions were probably stressful Paranthropus and that they had to adapt to survive. ”

The Drimolen site and the nearby Swartkrans in South Africa. Photo credit: Courtesy Andy Herries

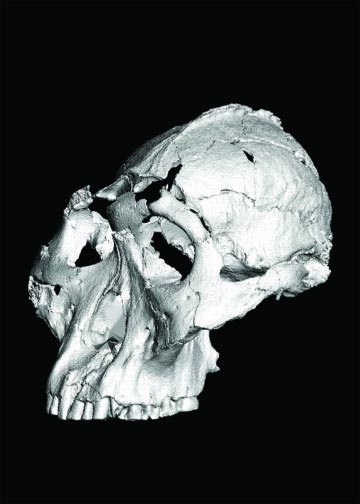

The new specimen discovered in Drimolen, identified as DNH 155, is clearly male, but differs from others in important ways P. robustus previously discovered at nearby Swartkrans – where most of the fossils of this species have been found.

The evolution within a species can be difficult to see in the fossil record. Changes can be subtle, and the fossil record is notoriously incomplete.

Usually the fossil record shows larger patterns, e.g. B. when species or groups of species are either found in the fossil record or are extinct. So this Drimolen discovery offers a seldom seen window into early human evolution.

The new specimen is larger than a well-studied member of the species previously discovered in Drimolen – an individual known as DNH 7 and believed to be female – but measurably smaller than suspected Swartkrans males.

Jesse Martin. Photo credit: WUSTL

“It now looks like the difference between the two sites cannot be explained simply as differences between men and women, but as population-level differences between sites,” said Jesse Martin, PhD student at La Trobe University and the Co -University first author of the study. “Our recent work has shown that Drimolen is about 200,000 years before Swartkrans. We believe that P. robustus has evolved over time, with Drimolen representing an early population and Swartkrans representing a later, anatomically derived population. ”

“You can use the fossil record to reconstruct evolutionary relationships between species, and that pattern can provide all sorts of insights into the processes that have shaped the evolution of certain groups,” Martin said. “But in the case of P. robustusWe can see discrete samples of the species that come from the same geographic region but have subtle anatomical differences at slightly different times. This is consistent with the change within a species. ”

Drimolen field students search sediments for fossils of small mammals. Photo credit: David Strait

“It is very important to be able to document evolutionary changes within a lineage,” said Angeline Leece of La Trobe University, the other lead author of the study. “It enables us to ask very focused questions about evolutionary processes. For example, we now know that the tooth size in the species changes over time, which begs the question of why. There is reason to believe that environmental changes are putting these populations under diet-related stress, and this suggests future research by which we can test this possibility. ”

Andy Herries, co-director of the Drimolen Project, said of La Trobe University, “Like all other creatures on earth, our ancestors adapted and evolved to the landscape and the environment. For the first time in South Africa we have the dating resolution and morphological evidence that allow us to see such changes in an ancient hominin line through a short window of time. ”

Evidence of rapid but significant climate change in South Africa during this period comes from various sources. Fossils critically suggest that certain mammals associated with wooded or scrubland environments are extinct or less common – while other species associated with drier, more open environments were local for the first time.

P. robustus skull. Photo credit: WUSTL

“P. robustus is noteworthy in that it has a number of features in the skull, jaws and teeth that suggest it was adapted for a diet consisting of either very hard or very hard foods, ”Strait said. “We believe these adaptations enabled him to survive on foods that were mechanically difficult to eat as the environment changed cooler and drier, resulting in changes in local vegetation.

“The specimens of Drimolen, however, have skeletal features that suggest that their mastication muscles were positioned so that they are less able to bite and chew with as much force as the later ones P. robustus Swartkrans population, ”he said. “Over 200,000 years, arid climates likely led to natural selection that encouraged the development of a more efficient and powerful feeding system for the species.”

Leece said that was remarkable P. robustus appeared around the same time as our direct ancestor Homo erectusas documented by an infant H. erectus Skull that the team discovered in 2015 at the same location in Drimolen.

“These two very different ways H. erectus with their relatively large brains and small teeth and P. robustus represent different evolutionary experiments with their relatively large teeth and small brains, ”said Leece. “While we were the line that prevailed in the end, the fossil record suggests that P. robustus was much more common than H. erectus two million years ago in the landscape. ”

Sunrise at the Drimolen field site, South Africa. Photo credit: David Strait

In a broader sense, the researchers believe this discovery serves as a cautionary story for the identification of species in the fossil record.

Large numbers of fossil human species have been discovered in the past quarter century, and many of these new species names are based on small numbers of fossils from just one or a few locations in small geographic areas and narrow time ranges.

“We feel that paleoanthropology needs to be a little more critical when it comes to interpreting variations in anatomy as evidence of the presence of multiple species,” Strait said. “Depending on the age of the fossil specimens, differences in bony anatomy may represent changes within lineages rather than clues to multiple species.”

Members of the research team at the Drimolen field site in South Africa. Photo credit: David Strait

Project Co-Director Stephanie Baker from the University of Johannesburg added, “Drimolen is fast becoming a hotspot for early hominin discoveries. This is evidence of the current team’s dedication to holistic excavation and post-field analysis. The DNH 155 skull is one of the best preserved P. robustus specimens known to science. This is an example of what careful, thorough research can say about our distant ancestors. ”

Reference: “Drimolen Cranium DNH 155 documents microevolution in an early hominin species” by Jesse M. Martin, AB Leece, Simon Neubauer, Stephanie E. Baker, Carrie S. Mongle, Giovanni Boschian, Gary T. Schwartz, Amanda L. Smith , Justin A. Ledogar, David S. Strait and Andy IR Herries, November 9, 2020, Natural ecology & evolution.

DOI: 10.1038 / s41559-020-01319-6